Blue Sky Solar Racing

In my second year at UofT, I joined the UofT Blue Sky Solar Racing team as an aerodynamics member. The Blue Sky Solar Racing team has competed in various competitions such as the American Solar Challenge, Formula Sun Grand Prix, and the World Solar Challenge in the challenger class. For more information about Blue Sky Solar Racing, you can check out our website or our Wikipedia page!

The Aero Design Process

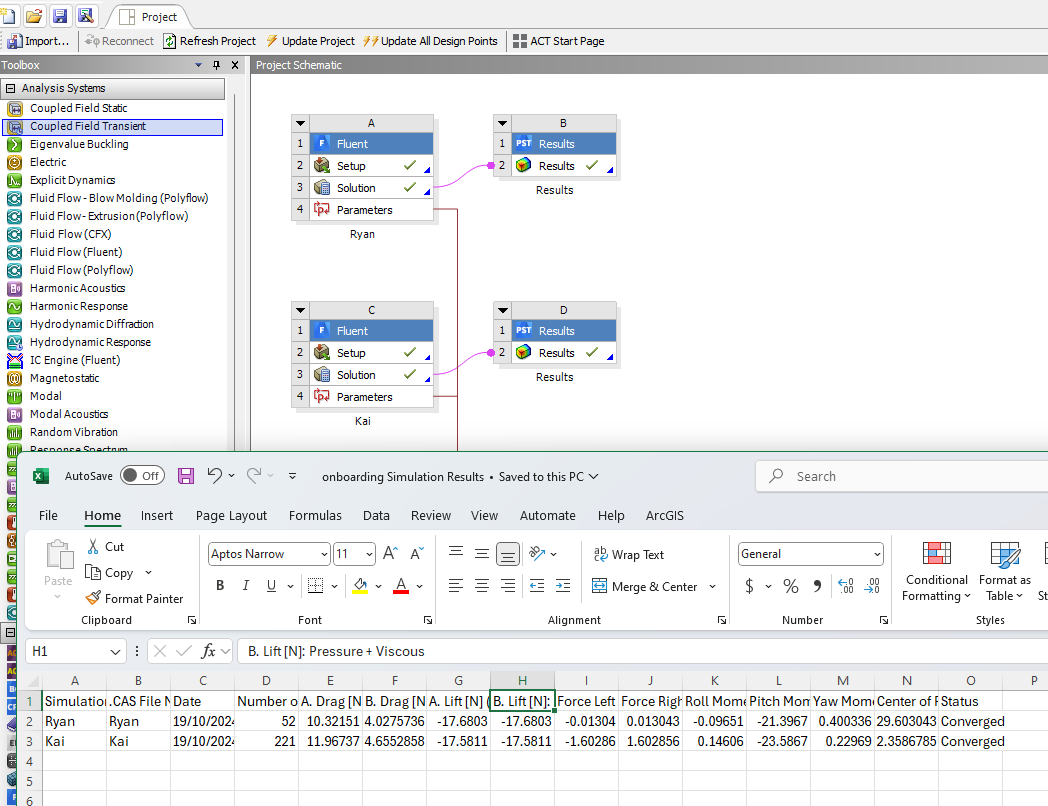

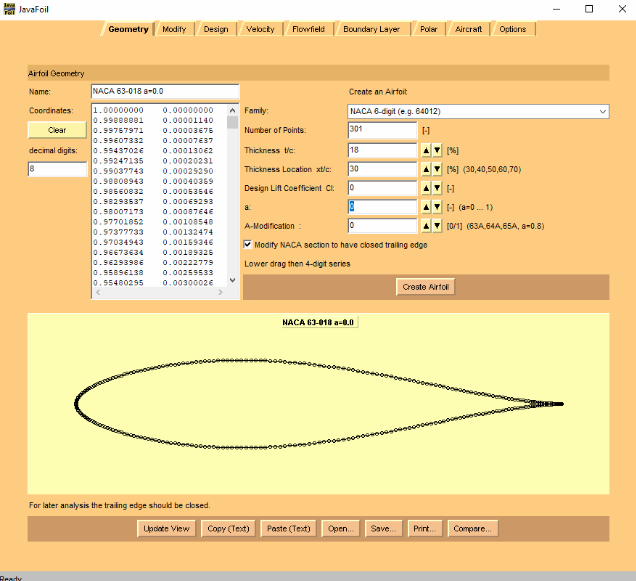

The first thing that I did as a part of the Blue Sky team is recruitment. During aero recruitment, we essentially learned about the general workflow for aero team members. This consists of CAD, meshing, and simulations. CADing at Blue Sky is done on CATIA Generative Shape Design. CATIA is useful for designing aerobodies as we can use the multi-section surface tool to create aerodynamic surfaces. Furthermore, identifying sharp edges where there may be increased drag or turbulence. Fidelity Pointwise is used for meshing, which is where the shape of the aerobody is accurately defined for running computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations. Finally, simulations are done using ANSYS Fluent. Thankfully, the Blue Sky Solar Racing has created a script, which has helped the team ease into using ANSYS for work. I am really glad that I got to learn different CAD software such as CATIA, as there are some mechanical engineering design jobs that do prefer prospective employees learn CATIA. Furthermore, learning ANSYS is a great skill to have for being attractive as a prospective mechanical engineering intern.

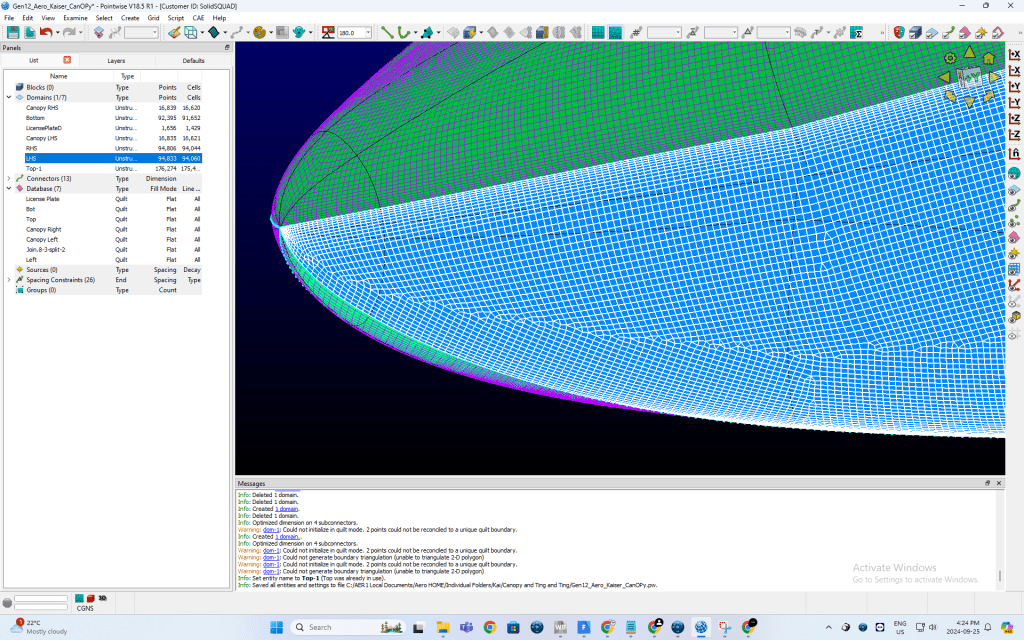

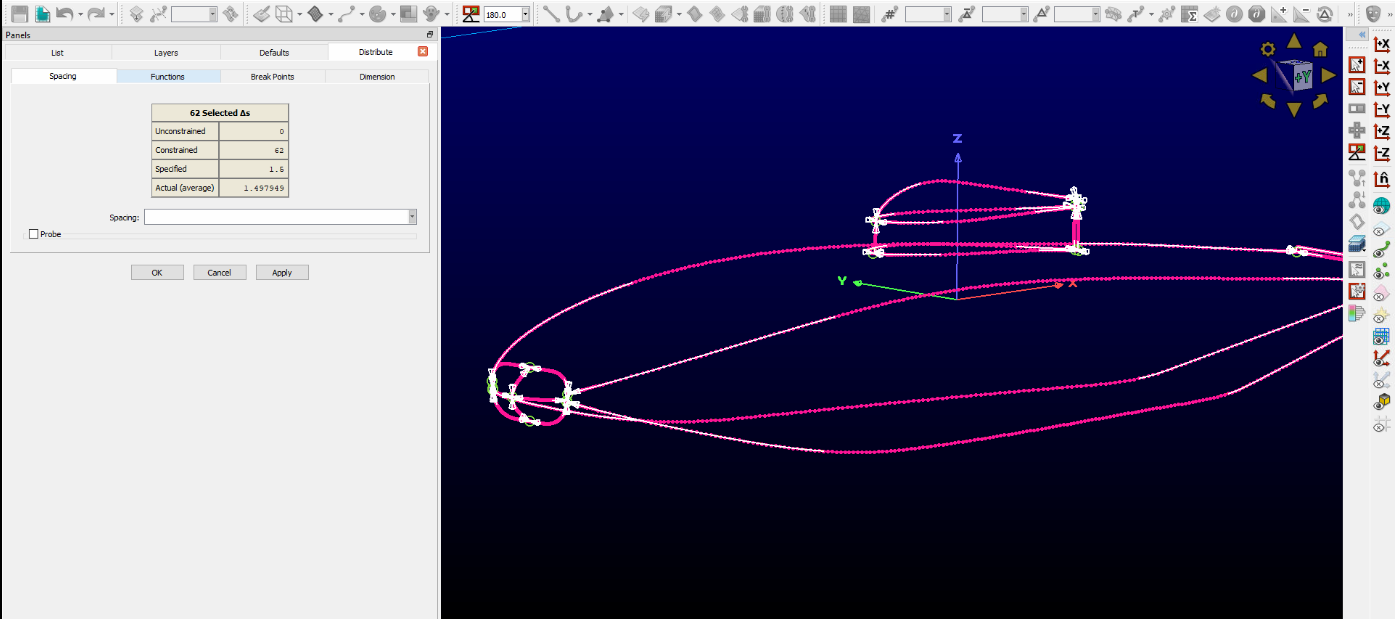

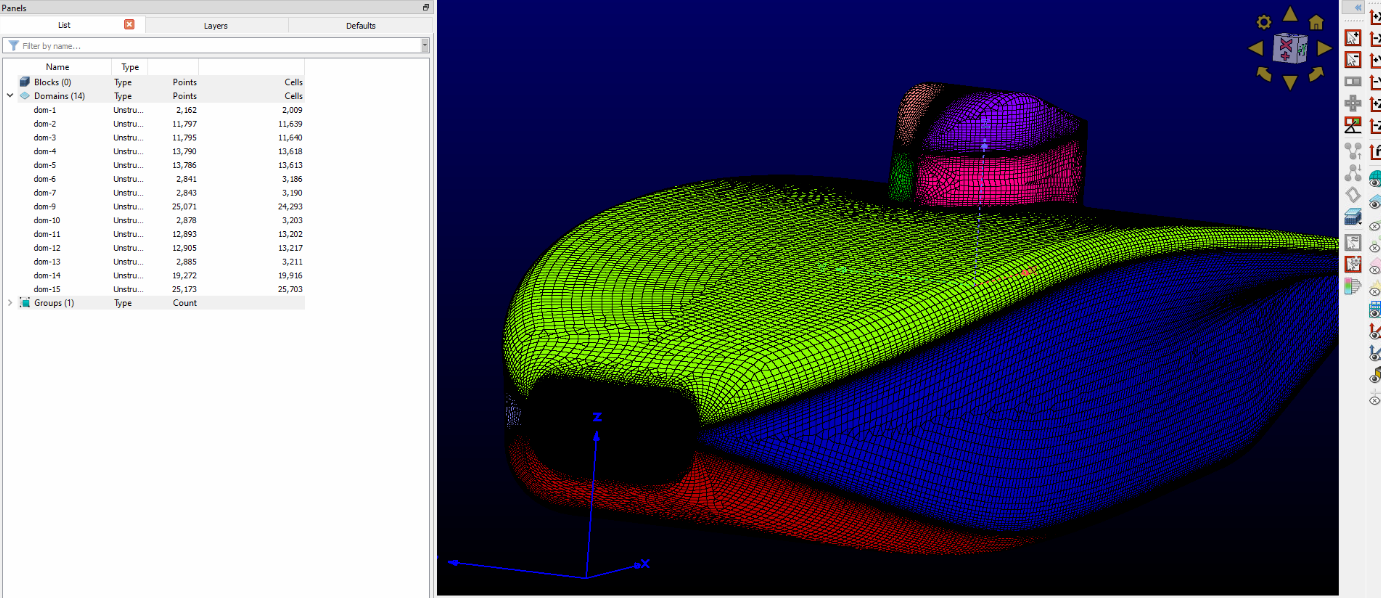

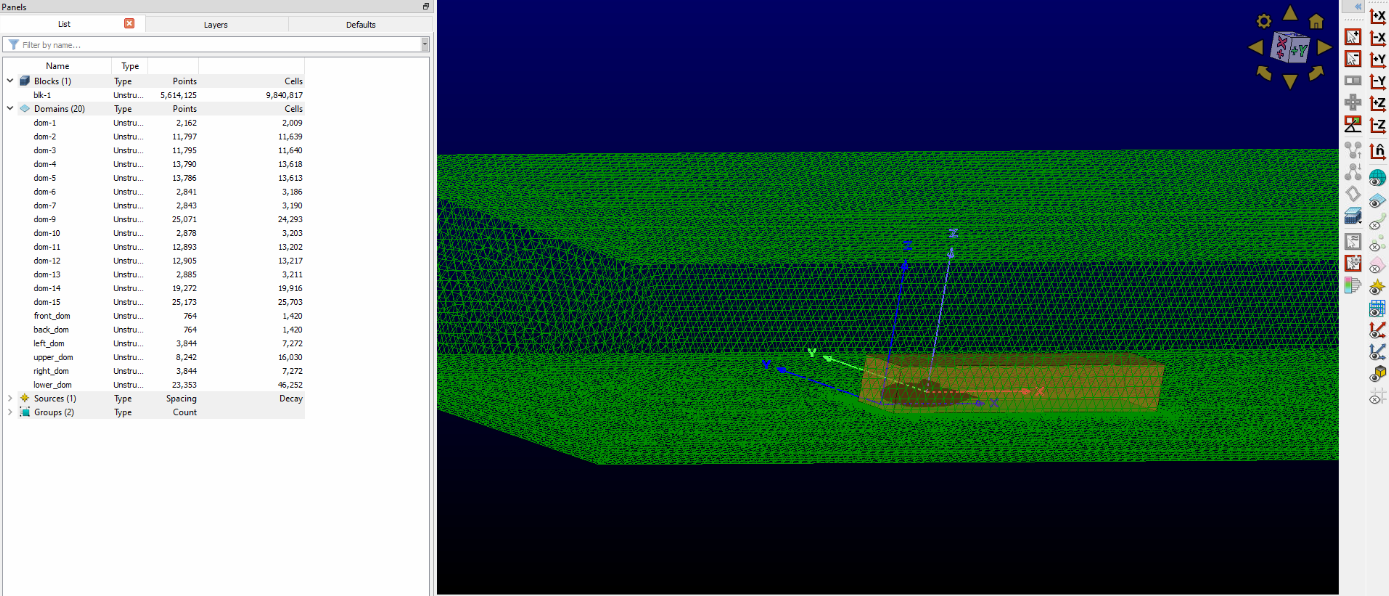

In my time on aero, I have done the same CAD, Mesh, Sim process countless times for various projects. As I have gone through this iteration, process, I have refined my ability to use each of Catia Generative Shape Design, Pointwise, and ANSYS Fluent. At first, I was quite clueless when it came to CATIA. It felt so weird to use a different CAD system than SolidWorks and it really challenged the way I thought about CADing. However, learning to do both surface modeling in CATIA and solid modeling in SolidWorks provides the benefit of seeing how different parts can be designed using the two techniques, and then choosing the approach that best allows me to capture the geometry of what I am CADing. As for Pointwise, In Pointwise, I’ve learned to deliberately troubleshoot and refine meshes instead of just doing what a tutorial said was good. Learning why certain things work like using growth spacing vs tanh spacing for certain connectors, or when to set the full t-rex layers to 1 or 0 really makes a difference in the quality of meshes I was producing. The more accurate the mesh is, the more accurate the sims will be, so it was critical that my meshing ability gets refined.

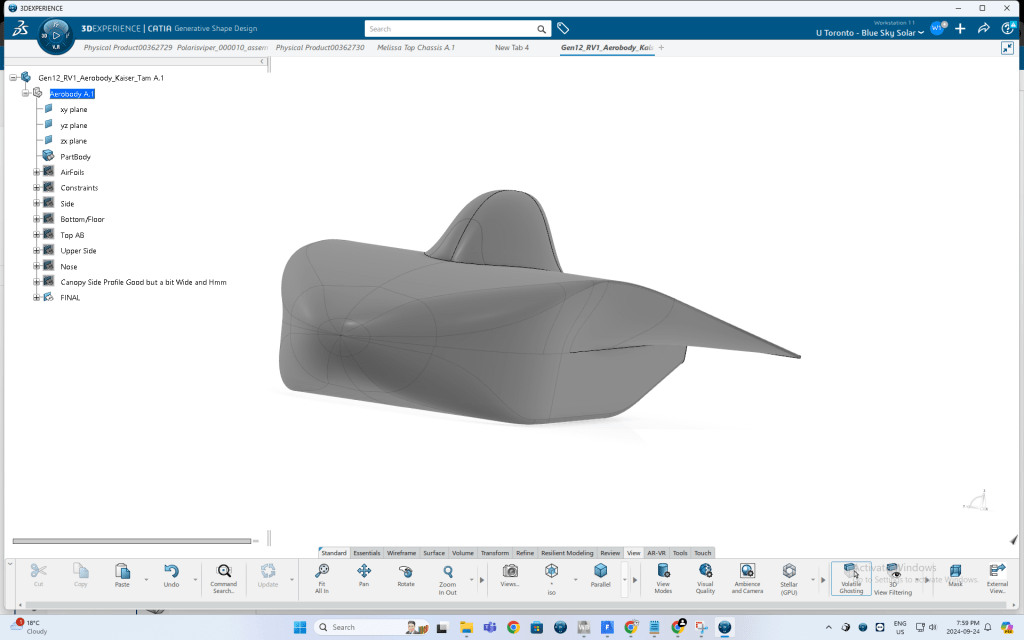

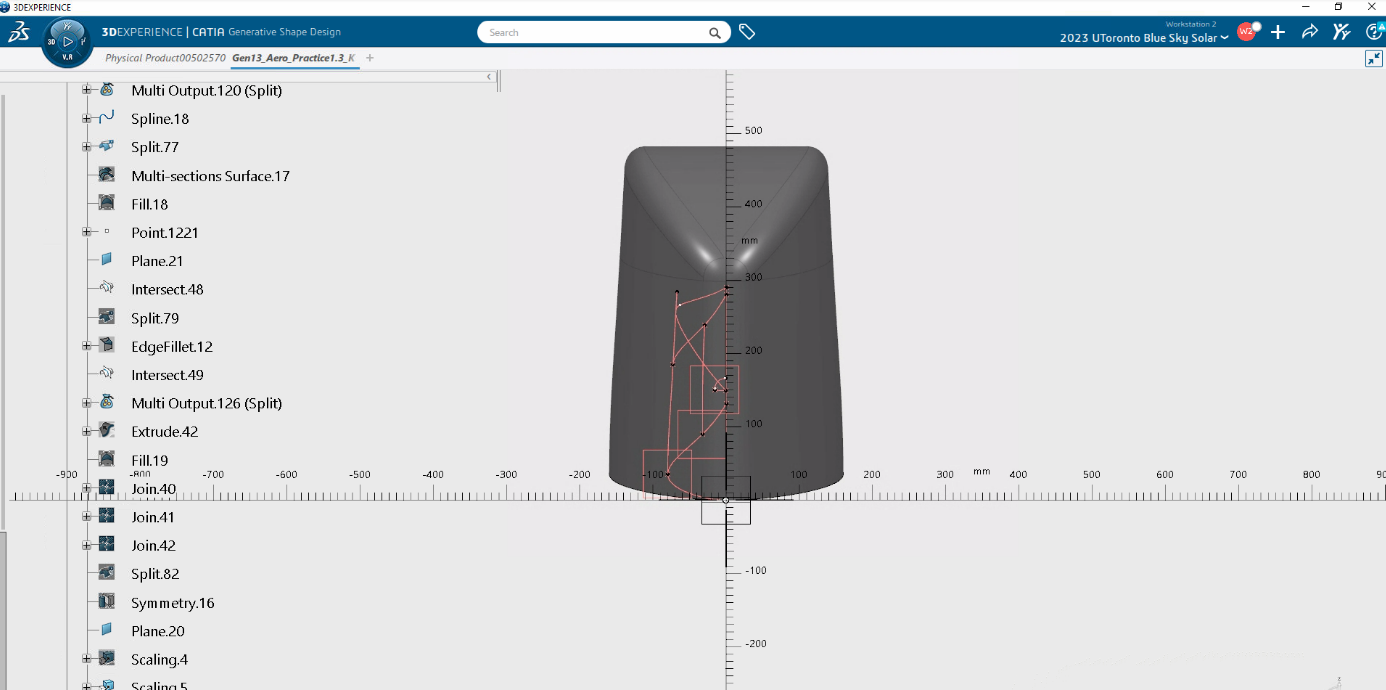

CAD Process

This section will go over how I like to use CATIA to do surface modelling to create potential solar car designs. CATIA is great for solar car design because the multi-section surface tool lets me create smooth surfaces based on specific supports and guide profiles. Furthermore, CATIA allows me to iterate quickly on my previous designs so that I can make adjustments to my CAD as necessary.

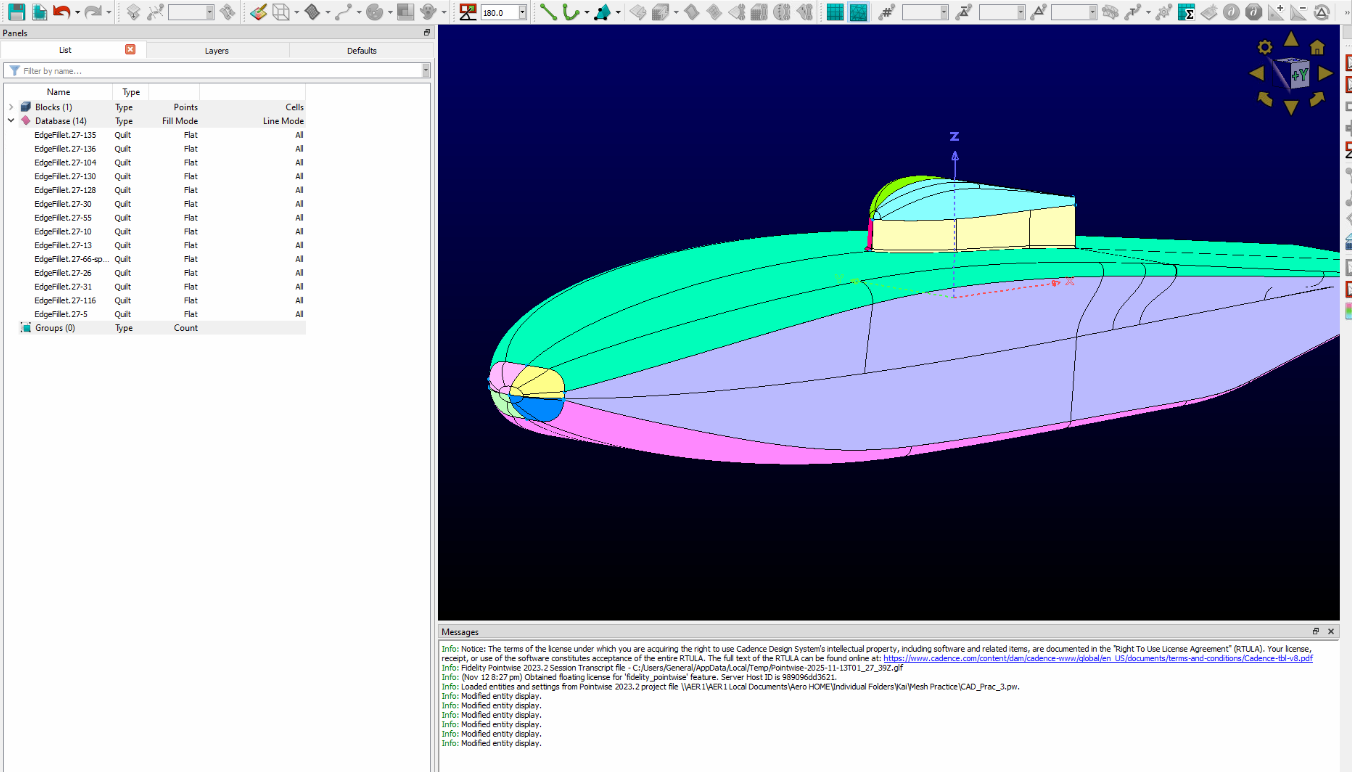

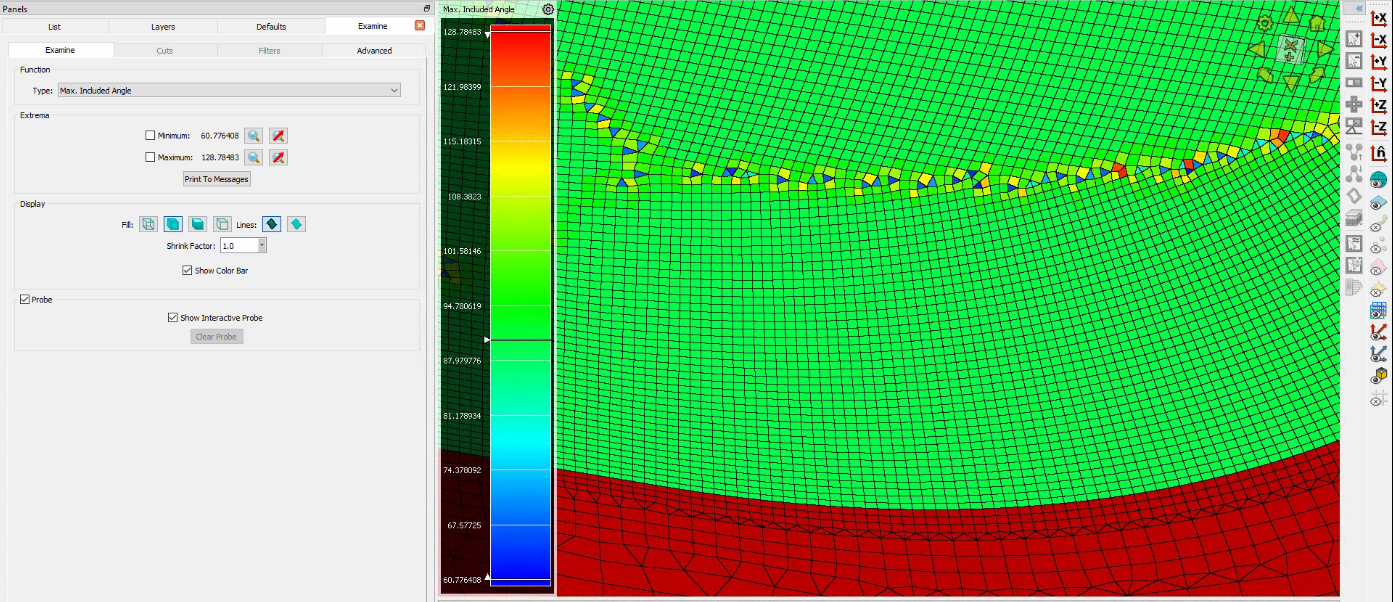

Meshing Process

Once the CAD is complete, it is time to mesh the car. Since vehicles have a complex shape, and hand calculations would be tedious, it is important to create a mesh that accurately represents the car’s geometry to prepare it for a computational fluid dynamics sim on ANSYS. If the mesh is poorly done then the car may not sim at all. And if the car does sim with a poorly constructed mesh, the finite volume method will inaccurately predict important aerodynamics values.

Wind Tunnel Testing

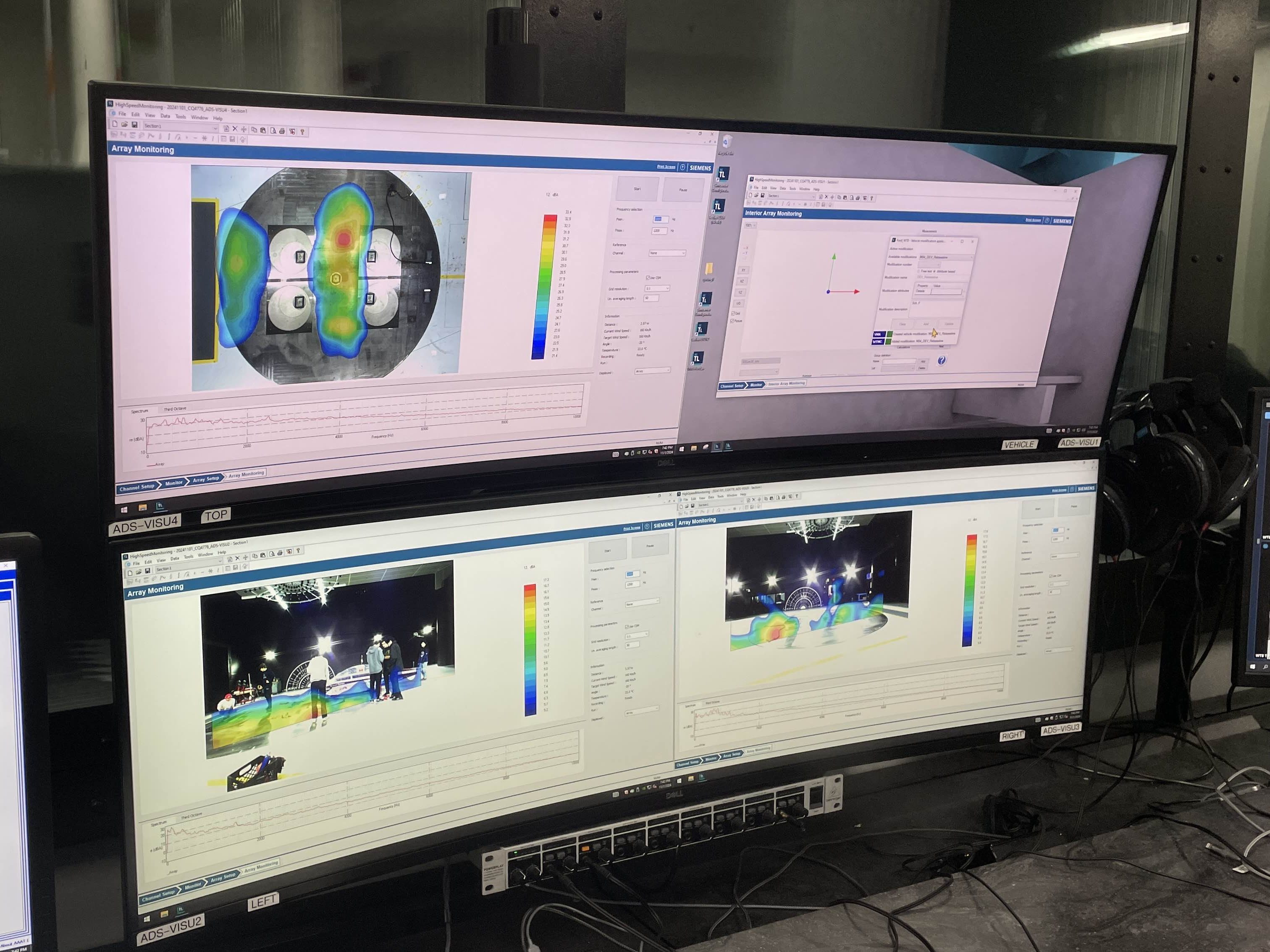

One of the first things I got to do as part of the Blue Sky team is help with aero validation. We wanted to do this to compare our simulation results from the Gen 11 vehicle on ANSYS Fluent to actual values. To do this, the team went to the Ford Drivability Test Facility (yeah, it’s called DTF) Wind Tunnel No. 8 to test out the Gen 11 vehicle, Borealis. It was really cool to go to the Ford Drivability Test Facility because it provided insight into a potential career for a mechanical engineer that also involves aerodynamics.

After completing the wind tunnel testing, our team then went back to Toronto to report on the results of the testing. The wind tunnel testing provided significant insight into how our CFD model compares to real-life results. This report will provide future generations of Blue Sky Solar Racing with data on force measurements at varying speeds and yaw angles to make design improvements on future solar vehicles. Areas for aerodynamic improvement are identified based on the observations made during the tuft and laser sheet flow visualization.